- Scotland

- Content

News

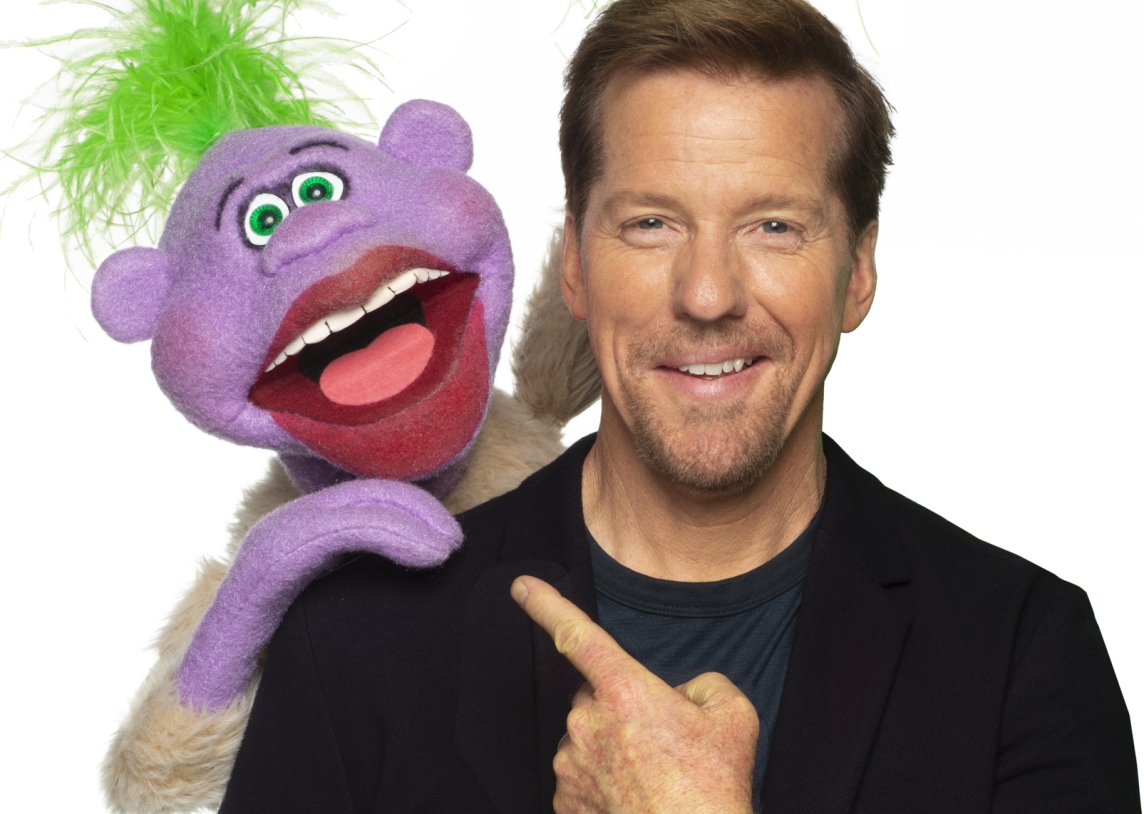

Jeff Dunham - Review

Gareth K Vile considers the comedy of the thrown voice, while Jeff Dunham follows the proud tradition of Punch

In a review from around five years ago, the ‘family conscious’ website Common Sense Media castigated Jeff Dunham for profanity and blasphemy: his Wikipedia entry, however, relates his remarkable successes. As a ventriloquist, Dunham’s success in the arena of stand-up comedy is a rare thing, and his audience at Glasgow’s SECC is clearly familiar and wildly enthusiastic for his blend of stand-up and puppetry. The condemnation from Common Sense Media, which appears to rate performers on their moral character, is unfair in so far as it fails to distinguish between the personalities of his dummies and his own identity. And it is in this gap that Dunham’s work is most intriguing.

Before the show begins, a series of Dunham related slides are projected onto the large screen: a fan look-alike contest, trivia about Dunham’s career and his relationship to the puppets, suggestions for social media follows and facts about individual puppets. Much of the ventriloquism is based on familiarity with the characters, whether a Jalapeno on a Stick or a red neck alcoholic, or Walter, a curmudgeonly old man whom Dunham uses to channel some relatively mild criticism of the United States’ current president. The introductory routine allows Dunham to establish his own identity (husband, father, son to an aging mother) with bursts of darker wit and observational tales about his young twin sons. Despite some sardonic comments on death and senility – interspersed with Dunham’s ironic doubts about the suitability of the humour – Dunham pitches himself as a loving father and husband, an ordinary man who just happens to be an internationally famous performer.

Before he gets the little people out of their boxes – the mechanics of puppetry are presented in a down to earth manner – Dunham offers something between a trigger warning and a passive-aggressive complaint about ‘cancel culture’. It’s all a joke, he insists, and please don’t be offended. We are here for escapism, and this is not a political event. It is a version of the centrist defence of comedy, rolled out by acts before they start punching down on minority groups. It is as disingenuous in Dunham’s mouth as it is in the mouth of Dave Chappell or Maureen Lipman. Satirising presidents and ‘redneck’ culture – or having a character called Achmed the Dead Terrorist – is inherently political. However, at least Dunham’s disavowal of intended offensive provides an interesting perspective on the use of the puppet around contested cultural values.

Achmed is probably the most problematic puppet: although Dunham has claimed he is not a Muslim character, he speaks of women in burqas and an ideological disagreement with Isis. He is more of a vehicle to discuss ideas around identity than the specifics of geo-politics and relies more on audience interaction for humour than obvious racial stereotypes, although his character biography (he blew himself up trying to set an explosive) leans into a simplistic reading of the terrorist driven not by specific injustices but a generic desire to attack Western Civilisation. Yet he is sympathetic: even his violent catchphrase is received with ecstasy by the audience, and he leads the crowd in a sing-along. Dunham works hard to depoliticise Achmed, throwing in plenty of COVID jokes and mocking the audience’s Scottish accents. And, unlike Walter and Bubba J, his appearance lacks the cartoon intensity that recalls the ventriloquist dummies of the past, and their alarming tendency to come to life and kill people.

Bubba J is a straight forward parody of a North American redneck: his feature are exaggerated like a cheap caricaturist’s portrait but with an attention to detail in ugliness. Like Achmed, his apparently confrontational personality is tempered by the warm relationship between puppet and puppeteer. Bubba tends to say stupid, rather than obnoxious things. Walter, however, is a more sophisticated construction. Having noticed his physical similarity to Joe Biden, Dunham has him impersonating the POTUS. Yet he never really strays into satire, beyond noting that Biden is quite old and has senior moments. There is a level of mimesis in Walter (a man provides the voice to a wooden puppet, who pretends to be a third character) that would give Plato a headache.

Yet in all of the puppets, Dunham negotiates a distance from the material that he is presenting. A joke about terrorism – even the sympathy the terrorist gains through his quick wit and blunt honesty – is projected onto the puppet. Walter, already grumpy and antagonistic – provides a critique of the POTUS. Bubba can make fat jokes, and Dunham can corpse and look aghast. It is all about the plausible deniability. This makes for a better defence against censorship. The puppet becomes the outsider, the fool who can speak, if not necessarily truth, the excluded ideas. Even though Dunham wrote the joke, or thought up the ad-lib, built the puppets, operates the puppets, he performs a complex relationship with them, apparently allowing them the freedom to find their own humour and identity. Certainly, the humour is softened by the puppet’s delivery.

Perhaps Dunham’s remarkable success is based on this dichotomy. The Glasgow audience – despite the city’s history of being a tough crowd – rolled over and let Dunham tickle their belly and his humour, which can veer between mildly blue and dad jokes, as well as more trenchant observations and sharp one-liners, is lent a surreal edge through the ventriloquism. While he never explicitly plays with the levels of mimesis – to be honest, this level of analysis feels ill-suited to Dunham’s warm, everyman presence – the show speaks to the potential of the puppet as a subversive humourist. Never quite acknowledging responsibility for the content, always flittering between cute and cutting, the puppets become something like a supernatural voice, a non-human perspective on human absurdity. Like the British Punch, Achmed is an antihero, a performer absolved of the moral responsibility forced on humans, finding a place to be both subversive and comforting.

Parent reviews for The Jeff Dunham Show | Common Sense Media

Maureen Lipman: Cancel culture could wipe out comedy - BBC News

Cancel culture killing comedy? What a joke | TV comedy | The Guardian