News

The Contemporary Palle

By Eva-Liisa Linder

Theatre Researcher

Palle Alone in the World is one of the books from your childhood, the central image of which will haunt you your whole life. The phrase “like Palle alone in the world” seems to be firmly rooted in the collective consciousness of those who are currently middle-aged, for example, when they are walking around town in the early morning. Jens Sigsgaard, a Danish psychologist, has insightfully depicted one of the most intense conflicts of life – the one between selfishness and taking other people into consideration. The story about Palle was inspired by a survey in which a thousand children were asked what their secret wishes were. The primal survival instincts in their untamed selfishness are clearly revealed in children, who have not yet been conditioned by society’s expectations and who are thus, so-to-say, unpruned plants.

Simultaneously, the book about Palle questions the boundaries between children’s literature and general literature. It has been placed in the category of philosophical children’s literature, but it could also be considered a general philosophical work, just like several other children’s stories, such as The Little Prince, the Moomin stories, and Andersen’s fairy tales. Throughout history, Palle’s loneliness has acquired different meanings. At the time when it was written – in 1942 – the World War was being waged. Just a year later, in 1943, Sartre expressed the idea that “hell is other people” in his play No Exit. In the wave of post-war philosophy, both the idea that “man is dependent on the reflection of himself in another man’s soul” (Gombrowicz) and responsibility for the Other (Levinas) started to resonate strongly.

In the Estonian cultural space, the best-known interpretation of the story about Palle is the Soviet-time puppet animation film Peetrike’s Dream (1958), where the visual techniques conveyed the contrast between the totalitarian and the capitalist world – in the latter, goods were abundantly available, as Tristan Priimägi insightfully mentions in the playbill of the production. In the present day, parallels can be drawn between Palle’s story and the recent pandemic, which aggravated the feeling of loneliness in (school) children.

The Palle production of the Estonian Theatre for Young Audiences (ETYA) has shed the excessive burden of history. First and foremost, it has the feel of a light-hearted and clever contemporary story. Actor and director Karl Sakrits, who studied performing arts at the Viljandi Culture Academy, has also in the previous productions of the ETYA succeeded in finding phenomena that resonate with children, such as umbrellas and ghosts. His handwriting exudes simplicity and calmness, characteristic of a country boy and so highly valued in a world full of hustle and bustle.

The other director of Palle, video designer and composer Mait Visnapuu, is known as a sound director. Simultaneously being the head of the sound and video department of the ETYA as well as the Recording Arts supervisor and a lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, he has in-depth knowledge of technical art. To the observer, it seems that the new directing tandem is pedalling energetically, which raises the hope that they will cover a long distance together.

Director Sakrits is also the author of the dramatization of Palle, bringing the events to the modern day, as if into the life of a boy who lives in Tallinn. The little Palle speaks in a simple and natural way, using authentically colloquial language. A bonus is Palle’s voice, which belongs to Gustav Visnapuu, a primary-school-aged boy. The cutely matter-of-fact speaker instructs the spectators to turn their phones on the silent mode before the performance starts. With a warm confidence, the voice continues to pass on Palle’s internal monologues, being the third support pillar of the production, along with the puppetry and the video. The upbeat boy’s voice renders a human dimension to the events, combining the puppet motion and the video motion into a whole. The warm sound design (by composer Mait Visnapuu) reassures the audience that the situations that seem life-threatening will not end tragically.

The action on the stage proceeds in a linear and logical way. The Palle puppet, having a big round head and eyes that have a gleam of sunshine in them, wakes up in his bed. The video pencil keeps drawing new things on the stage: a clock, a sink, and a ball for playing. The boy does wonder, “Where are Mum and Dad?”, but the next moment, he is already jumping on the bed, eating candy, and enjoying his freedom.

Not finding breakfast awaiting, the little boy grabs organic milk, organic cereal, and unrefined cane sugar, the way he has seen his mother do – cute irony directed at the lifestyle of Estonians who are into organic goods. But, alas, the porridge on the stove drawn by the pencil starts boiling over; and the cooking experiment that has landed on the floor does not taste yummy. The daring boy goes outside to look for his parents. Apartment buildings show up, as well as long city streets, complete with bus stops, traffic lights, a bank building, and a theatre building.

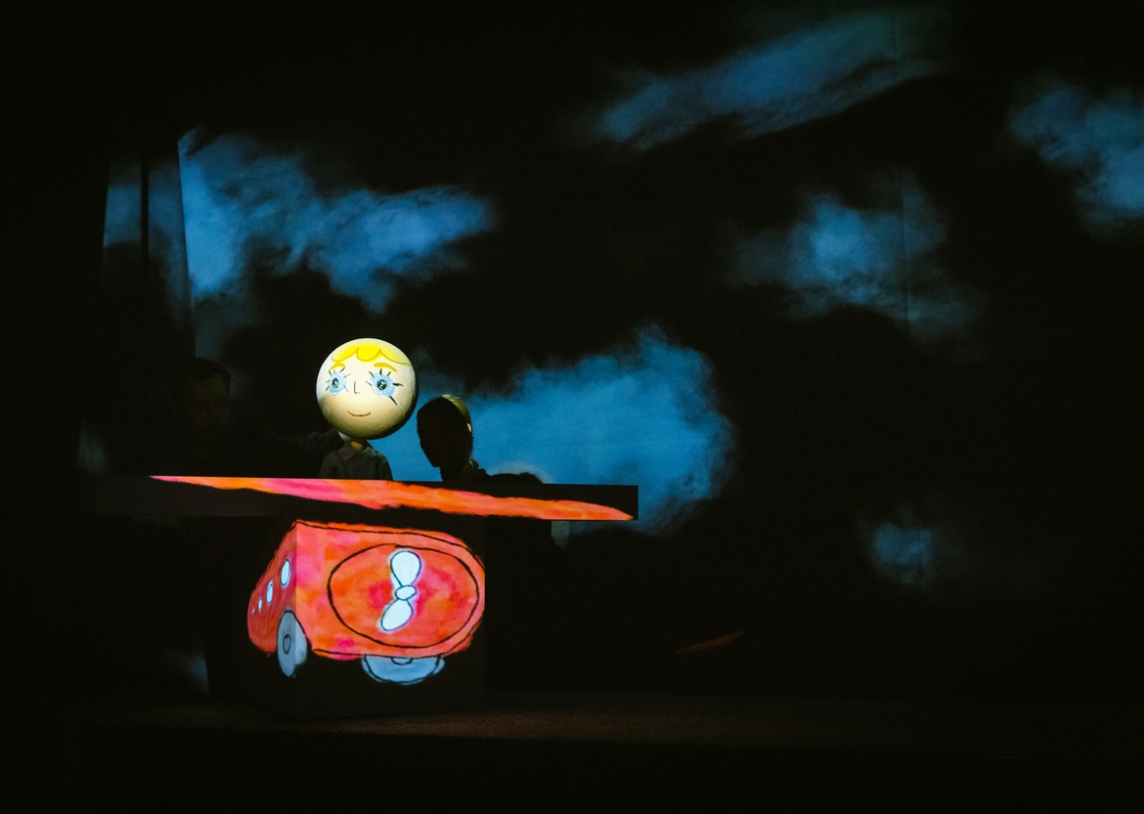

The performance is built up on a technologically ingenious and well-functioning symbiosis between a realistically moving puppet, the video world, and a warm child’s voice. Palle acts in the middle of the virtual world with the self-confidence characteristic of most kiddos who are born with a tablet in their hands. Throughout the whole performance, the invisible story pencil draws items and rooms in retro-aesthetic style on black cubes: the interior of a home, the buildings and streets of a city, followed later by a tram, a plane, and outer space (designer: Mikk-Artur Ostrov, animator: Meeri-Ann Ostrov).

Merging into the dark background, the puppeteers (Katri Pekri, Laura Nõlvak, Jevgeni Moissejenko, and Karl Sakrits) smoothly move the puppet and, with precise movements, lift the dark boxes into the right places, so that the pastel-coloured video pencil could paint one new world after another, without making the stage cluttered. A smart puppet theatre. A smart theatre. I’ve waited for a long time for such an animated innovation to show up in the Estonian puppet theatre.

When it comes to the plot, it gradually turns into a suspenseful ping-pong game between the excitement of aloneness and disappointment. It’s fun to break down the boundaries of society. To jump into a puddle. To walk on the lawn in the park. To race through the city with a shopping cart. To collect some money from the bank. To fill the cart with all sorts of goodies in the store. However, the next moment, Palle realises that there is nothing to do with the shiny gold coin at the cash register, because there is no cashier. Money has lost its value.

The joy of discovery, carried by the sentiment that “I am alone and can…”, is headed towards a collision with the rock of disappointment. There is no need to share your toys with anyone – every child’s dream! – but at the same time, no one is helping you push the carousel around. Sadness seeps into Palle’s voice as he calls out, “Hey, where are you, people?”

Doubts are reflected in the visual techniques: the surroundings start to shake, the events take on dreamlike twists. Palle boldly starts steering a tram, but his little hands are not steady enough. The collision with another tram exposes a helpless child: “Mum, I have an ouchie.” The biggest wish has turned into the worst nightmare. “Hell is other people” turns into the realisation that “hell is the absence of other people”.

However, the fantasy that has started won’t end. Palle spirals higher and higher in a red plane. Moving stars are sprinkled into stage space. The spectators are being taken along for the ride in outer space. The oval hall of the ETYA has suddenly become the infinite universe. The cathartic starry sky scene from the historical Põrgupõhja (Hellsbottom) production comes to my mind. A good example of how minimalist aestheticism can result in the maximum outcome. Less is more.

However, this time, Palle’s fall ends with his waking up. The boy that gets out of bed looks so different – it’s a more mature, more sensible (school) boy. The third Palle puppet. Mum and Dad are next to him and promise never to leave him alone. The end makes me shed a tear.

While Peetrike’s Dream became the opening act of Estonian animation, the Palle production could open a new chapter in the puppet theatre – one in which the animated solutions are a valued part of the toolbox. Just like the digital world is a part of children’s lives. Even though the target group of the production is children starting from age 3, such a flight of fancy with its holistic aesthetics resonates with the spectator of any age. Half an hour of high-quality theatre.